Technology of transcendence (a shared ritual)

Schrijf je tekst hier...

Kibwezi, Kenya, 5/8/2021

On the second day, after we have sat on the wooden bench under the tree for seven hours, Nguti’s oldest son calls us into the space of the rituals. Yesterday, we were sent home after four hours. Snake Man, who had guided us to this place, had asked too many questions, Nguti found, and we had taken a picture of the residence which – while it didn’t show any people – included the flag, a red, white and black banner on a twig placed next to the big tree. Nguti told us that it is the official flag for a witch doctor. It had been Snake Man’s responsibility to make sure it is not photographed, “he knows the rules” she argued. With much agitation we were chased away and told that we can come back another time, but without Snake Man. Not a straightforward task, as the precise location of Nguti’s house is not generally known and we are not supposed to reveal her whereabouts and practices to arbitrary people in the nearby town, as many Christians are strongly opposed to witchcraft-related practices.

After we are called by the son, we enter a small hut, constructed out of red, unbaked clay bricks, a common method of building among the Akamba tribe in this region. Through a narrow hallway, in which Nguti’s other son is sleeping on an old sofa, we reach a dark room in which the healer – or ‘mundu mue’ – is awaiting us. While we were outside she had come to us several times already to speak about a dream she had about us, a story about a white man who once lived in the area, and her grief for one of her sons who recently died. A small and frail, yet powerful woman with clear, energetic eyes, she seems very old and rather young at the same time – we can’t tell how old she really is and don’t want to ask.

Nguti sits on a cracked plastic chair amidst a collection of small objects: a broken calabash, the remains of a book, a small frame with a broken mirror, a bottle of beer, a pile of half-smoked cigarettes. On the floor in front of her, we finally see the device we have been talking about for about a year now: the nzevu, a one-stringed instrument that is used by healers of the Akamba tribe, the tribe Greenman was born into. Unfindable on the internet and hardly documented elsewhere, the nzevu is only used in rituals, not in public music performances. While our backgrounds are very different, we have a shared interest in getting to know this instrument, based on our long standing exchange about the relationship between technologization, everyday life and colonial heritage. Greenman grew up in Korogocho, a low-income neighbourhood in Nairobi, in an Akamba family that had moved to the city to find work. Dani was raised in Oost-Souburg, a small town in the Dutch countryside, experiencing the transition from the rural life of his grandparents towards urbanized digital culture in the 1980s and 90s. Since 2016, we have explored ways to reappropriate discarded electronic devices, together with Nairobi-based artist Joan Otieno and a varying group of collaborators working in arts, electronics repair and academia.

Central to Nguti’s practice is her entering an altered state of consciousness, in which she consults or collaborates with the spirit world to resolve a client’s problems or challenges in life. During a ritual, the nzevu is used to play very short, repetitive patterns for extended periods of time, in order to bring the mundu mue into a state of trance. In addition, she consumes various substances, such as snuff tobacco, beer and multiple cigarettes that are smoked simultaneously with the tip inside the mouth. Once the trance condition has been reached, the healer engages in communication with the spirits. In this, the nzevu also plays a central role. It is listened to in silence without being played. The resonances of the calabash that forms the instrument’s body are observed to hear the voices of the spirits.

We do not wish to share the contents of the divination Nguti did for us here, as we consider these a private matter and beyond the scope of this article. Rather, the reason we discuss our experience concerns the role of the nzevu as a cultural artefact. It is used as a device to reach an altered state of consciousness and to establish communication with the spirit world, rather than an instrument for musical performance as an artform in the contemporary Global Northern sense. Hence, drawing from psychiatrist and anthropologist Roger Walsh’s (1989) writing, we suggest to refer to it as a technological device, a ‘technology of transcendence’ (p. 34) to be more specific. This explicit framing of a device like the nzevu as part of technological culture lies at the basis of our collaborative artistic research into the reappropriation of everyday digital devices, which we have conducted in various places in Kenya for the past five years.

The concept of technology, and the demarcation of the boundaries between what is colloquially perceived as ‘technological’ and what not, is politically charged. Cynthia Cockburn (1992) points out that the widespread exclusion of kitchen appliances and other domestic devices from what is commonly referred to as ‘technology’ has played a significant role in the propagation of the cultural stereotype that technology is a male domain of culture; a state-of-the-art hi-fi amplifier is commonly perceived as part of high-tech culture, a washing machine often isn’t. In a similar vein, we suggest that the exclusion of devices like the nzevu from the category of technology reinforces a ‘myth of progress’ that originates from liberal-capitalist worldviews prevalent in the Global North. In this myth, technology acts as symbol for notions of rationality, efficiency, speed and progress connected to a belief that ‘new technologies will conjure away the immemorial evils of human life’ (Gray, 1999, n.p.) through boundless techno-consumerist expansionism.

This narrow and generalized approach to technology goes in hand in hand with the promotion of globalized, Silicon Valley ideological (Silverman 2018), product standardizations that alienate users from their immediate lifeworld with its specific cultural practices and environmental interactions. This becomes especially pronounced in many places in the Global South, where the disjunction between technologies’ functionality and local practices often is more abrupt. For example, the top down perspective maps in an app like Uber are often perceived as far from ‘intuitive’ and ‘user-friendly’ in a country like Kenya where the practice of map reading is not as deeply anchored as in countries that have a long colonial tradition of map-based navigation. Moreover, in many instances it is questionable to what extent everyday interactions with technological commodities actually adhere to the imaginaries of rational, high-tech processes they are commonly associated with. For example, are our engagements with social media platforms really a more rational way to spend time and engage with the world than taking part in a ritual with the nzevu?

The absence of technologies like the nzevu in commonplace imaginaries of technological culture also relates to Bruno Latour’s (2011) critique of the colonial distinction between supposedly naive fetish worship in West-Africa on the one hand, and European cultural practices believed to be based on facts and rational thought on the other. When we look more closely, it becomes clear that European traditions of knowledge production and technological development are not that dissimilar from African practices connected to fetishes and ritual objects. As Latour argues, the establishment of a ‘fact’ constitutes the end of a process in which a certain abstraction is attached to an object. This act of attachment actually constitutes a reversal of cause and consequence that is comparable to the process of creating a fetish object that is subsequently treated as having autonomous power.

Likewise, what currently tends to be understood in the Global North as factual science and clearly distinct from belief practices has often emerged in the context of an intertwinement with theology and spiritualism. An intriguing example is Isaac Newton’s unresolved quest to understand ancient Greek cosmology and the apparent conflict between electromagnetism and gravitation. In his explorations of this, Newton actually also practiced alchemy and he notably referred to his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687) as a theological work. Aspects like these have often been neglected in contemporary narratives on the origins of modern science, which emphasize a mechanistic ideology that precludes the possibility of a role for intelligent agency and cosmic information systems.

In the context of these deliberations, we approach contemporary technological commodities (digital and otherwise) as always already fulfilling a certain kind of mythical or enchanted role, albeit mostly in the context of the ideologies of neo-colonial consumer capitalism. This has been the starting point for our quest to find ways to reappropriate mass-produced digital devices in order to connect them to personal and local experiences, memories and worldviews instead. Collecting artefacts intercepted from waste streams or obtained on second hand markets, we try to find and develop alternate approaches to everyday technologies that divert from the uses and understandings that were foreseen by their engineers, designers and marketers.

Greenman Muleh Mbillo & Dani Ploeger, 2021-22

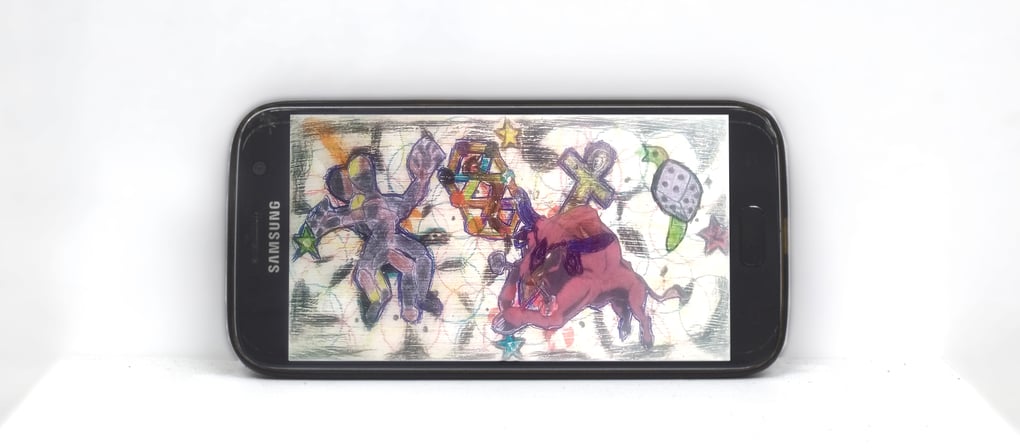

Dani Ploeger & Greenman Muleh Mbillo - Ûiiti ('the treatment'), 2022

Android app based on the nzevu, commissioned by House of Electronic Arts Basel as part of 'Net Works'